Data selection: preservation intervention points

Data selection is a complex topic. While it may be cost-effective to select only certain files for archiving, different files or versions may become more important to future researchers, and new tools might enable better analysis of existing data. For complex data types, such as sensory scans or video recordings, these issues become critical as raw data may undergo significant changes as it is transformed into the final product.

The concept of a “preservation intervention point” identifies instances in which data is changed significantly. This may include the point of capture, filter, transformation or dissemination. Preservation intervention points provide a “chain of evidence” for data and, ideally, allow for the capture of the source, the result, and the processes or methods that ensure the transformation is repeatable. Although preservation intervention points are clearly more applicable to complex data types, they are still important for other source materials, such as images, where processing raw data can cause significant changes in the final result.

The preceding chapters outline the minimal requirements for an archival strategy where data have post-project relevance. As highlighted, such a strategy should include:

- The identification and management, during project planning and data creation stages, of suitable file formats with clear migration paths for both preservation and reuse.

- The creation of adequate documentation and metadata to facilitate preservation and reuse, as well as supporting in-house administration and management during the project.

Once the long-term preservation of digital outputs of a process has been identified as desirable, then it is best approached as a task from the initial planning stages of a project. However, the identification of what files are to be preserved, and at which stages of the project lifecycle, should also be a key part of the project design phase and a component of the implementation phase in which the data is created or acquired.

Preservation intervention points

For complex data capture or analysis tasks, copies of the data should be archived after each significant step of the process. The notion of data selection needs special attention, particularly in a complex archaeological project where data is acquired through one or multiple techniques and then merged or reprocessed through a number of phases to create a final “product.” Where a project has a series of lifecycle stages such as decimation, aggregation, recasting, and annotation, through which data is transformed, as well as being migrated from format to format, then there may be more than one potential preservation intervention point (PIP).

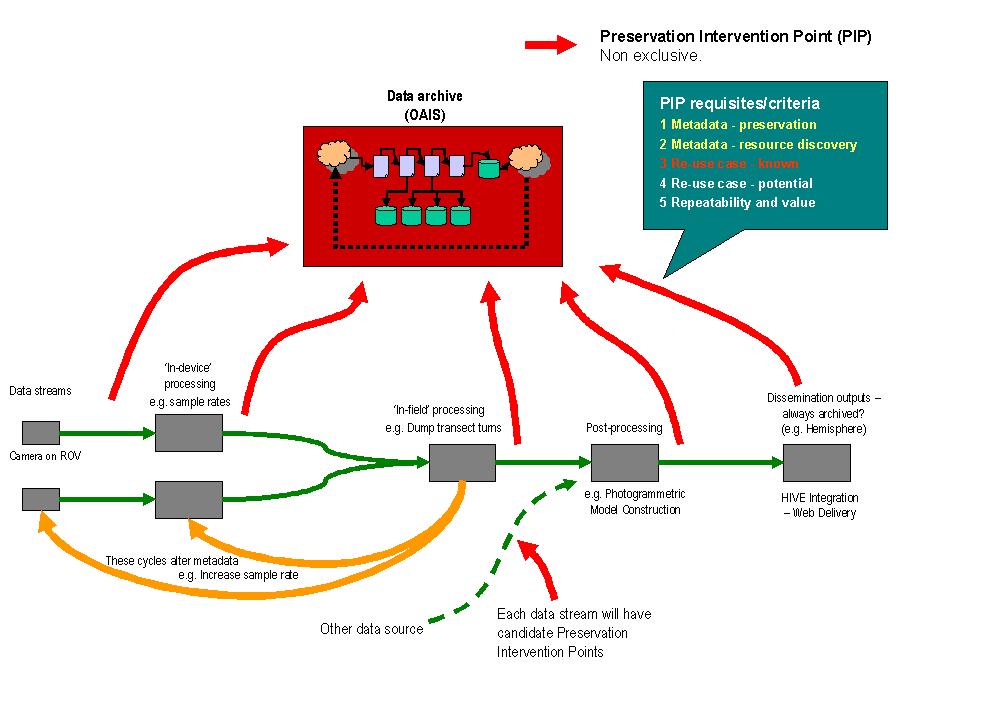

An example of this process is shown diagrammatically below (Figure 1, taken from the VENUS Project[1]). Proceeding from left to right, it can be seen that data streams are first generated by various (hardware-based) techniques in the field, and then undergo a series of transformations until the project dissemination products are created. The example stages indicated in the diagram are not comprehensive or definitive (even for the VENUS project), but include:

- Data stream generation—e.g., image capture from ROV cameras, bathymetric survey by sonar, device-specific locational information from DGPS or radio triangulation.

- In-device processing—e.g., sample rate—such as the rate at which images are captured—can be altered, or the lighting conditions can be altered. As it is variable (adjustable), this can be considered processing and can, depending on the device, require the discard of captured information.

- In-field processing—e.g., data is discarded as being outside the area of interest or sample rates are altered (either at this stage or by changing a device variable to alter in-device processing, hence the feedback loop).

- Post-processing—e.g., 1) XYZ coordinates are converted to a triangulated irregular network (TIN), or used to create a digital terrain model with derived data points; or 2) captured real-world dimensions are used to create an idealised three-dimensional model through photogrammetric techniques.

- Creation of dissemination versions—e.g., three-dimensional models are created for specific dissemination modes.

While it is clear that this in no way represents the totality of possible stages in an archaeological project life-cycle, it highlights the fact that data creation is often not a straightforward process and that there are a number of potential stages where it might be appropriate to create a preservation copy of the data.

Data documentation and metadata are also key components of the PIP concept. Although it is generally considered good practice that data be in as raw a state as possible for preservation, on the assumption that any subsequent transformations applied can be recreated with the right documentation, this is not the case for all types of data. One example where this approach fails is with photogrammetric data, where a series of images are used to construct a three-dimensional output. In such a case, a three-dimensional output (e.g., a model of an amphora or a DTM) may be constructed from a series of high-resolution images, but the process by which the output is created may be proprietary or unrepeatable (e.g., only repeatable within a specific software package). In this case, both the original images and the three-dimensional outputs would represent preservation intervention points. In more complex processes there may be even more preservation intervention points. Once all potential PIPs have been identified, they have to be judged against a series of criteria so that only the most appropriate PIPs for each data stream are chosen. The broad criteria by which PIPs are judged are:

- Preservation metadata—There should exist appropriate levels of preservation metadata so that the data are made reusable rather than simply preservable.

- Resource discovery metadata—There should be appropriate levels of resource discovery metadata so that data from each point can be meaningfully differentiated and distinguished from other parts of the dataset (this mostly applies to legacy data).

- Identifiable migration paths—There should be clear migration options for data at all stages.

- Reuse Cases—This is probably both the most important criterion and occasionally the most difficult to judge. Where the data is in a form that can obviously be used by other researchers, or in other contexts, then the question is simply whether reuse is likely to occur. The other complication is that, for certain types of data, a reuse case can be imagined as feasible even if it is currently not being enacted. An example of this would be a form of data that might lend itself to a post-processing technique under development, or merely envisaged as possible in the future (or an enhancement to an existing technique).

- Repeatability—Is the process that created this data repeatable? If so, an earlier stage may be an appropriate PIP; if not, then this intervention point should be selected.

- Retention policy—The data should match the retention policy of the target archive.

- Value—The cost of intervening to preserve data at this particular point, given that no project has an unlimited budget. “Value” here also means the value of the material to be archived, e.g., it might be worth preserving data produced by a repeatable process if that process were particularly expensive and difficult to reproduce. Value, therefore, has to do with balancing the perceived worth of the data against the cost of archiving.

The above criteria are not ranked in order of importance, and each has to be balanced against the other. The process of examining a project’s data lifecycle(s) should be performed, where applicable, as a consultation between the data creator and the archive.

In addition to the nature of the data itself, issues such as file size, storage costs, copyright and confidentiality may influence what data is selected for the final project archive. These issues are covered in the following chapters.

[1] https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/about/projects/venus/